French photographer Guillaume Binet talks about his experiences working in migrant camps in Libya and the importance of covering ‘difficult’ subjects.

zenith: Earlier this year you photographed inside Libya, in migrant camps and elsewhere. What were some of the challenges of this project – what kind of images were you hoping to capture?

Guillaume Binet: Libya is still deep in chaos. The armed factions are able to control the migrant camps because there is a lot of money to get out. They extort money from migrants in different ways. People can be freed if families pay a ransom. In addition, migrants are ‘rented’ to work outside, for example in construction companies, without obtaining wages.

No money, no room, no time in the media… This helps explain why so many tragedies go undocumented.

It is really difficult to obtain the multiple authorisations necessary to enter a camp – authorisation of the Ministry against Illegal Immigration (DCIM), authorisation of the militiamen, authorisation of the directors of the camps.

When you arrive in such places, you just wish to have a first glance. It is only step by step that you can go forward, deeper inside, until you meet someone, take his portrait, listen to his story. I had no preconceived idea before starting this work.

How did you feel when taking these photographs? What impressions were most vivid?

The hardest part was to work between the supplicating glances of the migrants – they are not allowed to talk to you and you are not allowed to talk to them, but they try, they whisper, they ask for your help. On the other side, you have the hard look of the guards weighing on you. You are stuck between the two, and you can only do a little. But you may be the only chance for people to know what is happening there. I feel that I have a responsibility to pass on their story. At the same time I feel helpless, because for these people I met, I won't be able to do anything at all.

One woman who had been there for nine months whispered to me some of the names she had received since she had left Guinea. A new one in every country she had been through: Binta, Myriam, Nabila…

The woman with the pink scarf

“I don’t know her name or even if she is still alive. The guards prevented me from talking to her. She was one of a group of women being held in the yard of a detention centre about 60 kilometres west of Tripoli near the coast. While they were attempting to reach Europe, they were intercepted on the Mediterranean by the Libyan Coastguard and brought back to the detention centre,” wrote Binet after his visit to a Libyan detention centre.

“Many of the women had severe burns on their legs. Sea water had splashed over the sides of the rubber dinghy and reacted with fuel that had been spilled on the floor of the boat where the women had been sitting. The prolonged exposure to this toxic mixture had caused the chemical burns.

The woman with the pink scarf had extensive injuries over her legs. She sat on the ground silently, her breathing shallow and the pain on her face palpable. The other women swatted away the flies landing on the damaged human tissue with their scarves. There had been an attempt to dress the burns with a dirty bandage.

One of the women whispered to me:

‘We’re scared. No-one wants to stay here. We want to go back home. They are hurting us. They hit us…’

But she stopped talking when the guards moved in closer.

For some of the women it had been their third attempt to escape Libya by sea only to be intercepted by the Libyan coastguard and returned to a detention centre. I don’t know what happened to the woman with the pink scarf. But without the medical care she so desperately needed, I doubt she is still alive.”

zenith: Did witnessing the situation in the migrant camps in Libya make you contemplate what kind of political solution could resolve the situation? Or what is your reaction otherwise?

Guillaume Binet: The situation of the migrants in Libya is a scandal, but I really think that it’s too easy for us to criticise Libya. Don’t forget that Libya is at war, the whole country is plunged into violence. They stop the migrants that we Europeans don’t want to welcome in our countries. Libya doesn’t have the capacity to do so in a decent way.

In many prisons, I met people who exhibited proudly their own retention ways (methods of detention? Not sure of meaning here). They were hoping to get money from the EU. Of course, this is not the solution. For me, it’s obvious that Europe should make a greater effort to participate in the fight against poverty in the world. Europe should also welcome more migrants than it currently does. Most economic studies show that it can be done without harming people already living in Europe. It’s really a matter of political will.

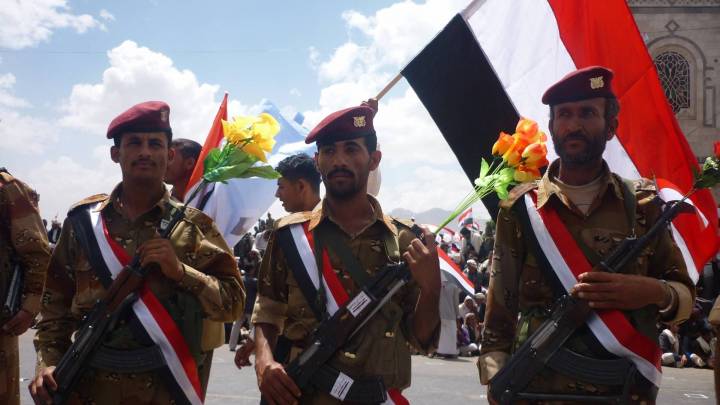

In 2015 you photographed the ‘forgotten war’ in Yemen. Do you see parallels between Yemen and Libya? What is the key to preventing the human tragedies taking place in these countries from being invisible in the West?

The situations in these countries are not well-known in the West. To understand what is happening there, you have to work at length to explain – you need time and space. Such things do not exist anymore in the mainstream media. The magazines have no more money to send reporters abroad. Each report I made, I had to figure out how to finance it. I was almost never sent by a branch of the media. I work alone, or with NGO support, and I sell the pictures afterwards. No money, no room, no time in the media… This helps explain why so many tragedies go undocumented.

Looking at your body of work, such as the French election or the US road trip, are there differences when you’re photographing in extreme circumstances such as in Libya?

No, I work in exactly the same way. I take pictures of what I see, generally with a 35mm, the closest to the human field of vision. In each field, the first quality needed is concentration. Also, there are different types of difficulties inherent to each kind of work, in any circumstances. In France, you now have huge difficulties taking a photograph of the first lady – the public relations team always denies access, and charges have even been pressed against a reporter.

See Binet’s photographs from Libya: