Damaged infrastructure and shortage of medicines in Yemen have created a perfect storm for the spread of cholera.

On June 13, Save the Children made the grim announcement that a child was being infected with cholera every single minute in Yemen. The waterborne disease was spreading like wildfire through the war-torn country, and health services were overwhelmed.

That was under a month ago, and in the time since, 100,000 more people have been infected with the disease and hundreds have died. Worse, the number of sick people is continuing to increase, and a World Health Organisation (WHO) spokesperson categorises the situation as “out of control”.

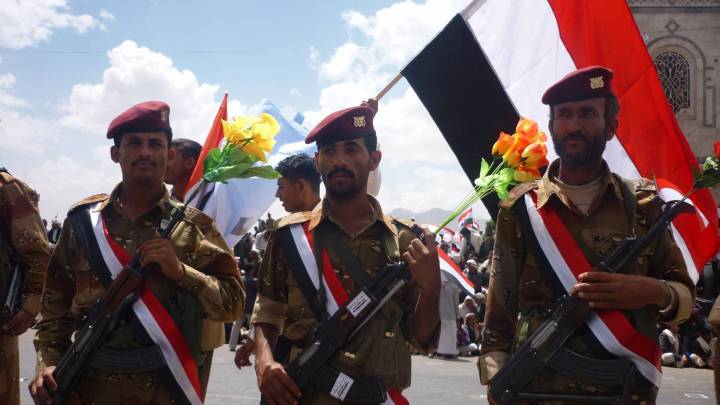

Yemen has always had the odd case of cholera in past years, but despite being impoverished, the country’s health system had managed to keep the disease in check. This all changed in March 2015, though, as war broke out between a Shia Muslim faction known as the Houthis and the country’s internationally recognised government. Exacerbated by a collapsed economy and sectarian tensions, the war quickly escalated and eventually Yemen’s neighbours began to intervene on behalf of the government.

Saudi Arabia in particular, as well as the UAE and several other Arab states began an aerial bombing campaign across huge sections of the country. While they claimed they were targeting military facilities and troop positions, their list of targets included public infrastructure, water facilities and hospitals. The US supports the Gulf states in this war, both politically and militarily. It sells these countries billions of dollars of bombs and weapons systems, and its navy helps enforce a crippling blockade of Houthi-controlled areas.

The fighting has more than ten thousands civilians, while soaring fuel and food prices have caused the average Yemeni to fear not just the bombs and bullets, but also starvation and easily treatable disease.

It was within this environment that cholera reappeared. Cholera is a bacterial disease which spreads through contaminated water. Within several days of infection, victims develop intense diarrhoea, causing them to rapidly dehydrate due to fluid loss. On average, epidemics kill 1-4 per cent of those infected, with children significantly more at risk. Yemen’s outbreak kicked into high gear little over a month ago and there are already horrific results.

“Hospitals are overcrowded to the point where patients are literally being treated on floors of corridors. Treatment at times requires medication beyond rehydration solutions, and many cannot afford it,” says Hisham Al-Omeisy, an analyst based in Yemen’s capital, Sana’a.

The current outbreak can be directly attributed to the collapsed health and sanitation networks within the country. “Two years of intense conflict have exacted a heavy toll on the country’s health system, as well as on water and sanitation services, and we’re entering the peak season for the spread of diarrhoeal diseases in Yemen,” explains Tarik Jasarevic , a spokesperson for the WHO.

This view is backed up by Iolanda Jaquemet from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which is also active in providing aid to the region. “They have no medicine, they have no fuel, the staff have not been paid in months and are not going to work anymore... it is a general collapse of health structures in the country, and the cholera is only the latest proof of this,” she explains. “The sewer system stopped working on April 17. Ten days later the cholera hit.”

The WHO is currently engaged in a massive effort to bring in much-needed supplies to directly treat and stop the spread of cholera. But it is far from enough. According to the most recent figures, more than 250,000 people have been infected by the virus, and over 1,560 have died. The number of people infected each day is still on the increase.

“A few weeks ago there was hope that the outbreak would peak. It has not peaked at all. Last week we were averaging around 5,000 new cases per day, but now we are well above 6,000,” says Jaquemet. “My colleagues in Sana’a expect [the number of infected] to keep rising by hundreds of thousands before it is stopped.”

Key to stopping the outbreak is providing Yemenis with consistent access to clean drinking water, as well as bolstering the country’s shattered medical infrastructure. This cannot happen while the Saudi-led bombing campaign (and indeed the wider conflict) continues. On June 19, the power lines to the main water supply system in Dhamar City were damaged as a result of military activity, cutting a million people off from clean drinking water, putting them at risk of infection.

“The epidemic hit us hard and spread like wildfire. The fact that many live in rural areas and where there’s a general lack of health facilities and medical assistance, has further exacerbated the problem,” says Al-Omeisy. “People are aware of all these factors, which are causing fear that is one step short of public panic.”

In the meantime, aid organisations including the WHO, ICRC and MSF are scrambling to provide basic services and train community volunteers in how to prevent the disease. They are calling on the international community for additional support and funding.

“The speed at which this outbreak is spreading is unprecedented in Yemen, and the local health authorities have stated that they don’t have the capacity to respond. The international community must come together to provide them with the support necessary to put a rapid stop to this outbreak,” says Jasarevic from the WHO.

But international action is predicated on international attention, something which Yemen is chronically lacking. Its conflict is often dubbed a ‘forgotten war’, and the fact that the country already hosts the world’s largest hunger crisis, with a massive 17 million people at risk of famine, has so far failed to galvanise international donors.

Lacking the headline-grabbing horror of Ebola or the ultra-violence of Syria, the situation in Yemen may sadly need to get far worse before it gets the attention it deserves.