Foreign firms in Israeli settlements in the West Bank are the object of much international criticism. SodaStream, the global leader in carbonated water, packed its bags and relocating to the Negev Desert. Was this a success for Palestinians?

The other day I felt a bit uneasy. We had friends visiting, and with the wine I served a pitcher of water. That's when it happened. “Did you fizz it?” our guest asked. With Sodastream, for instance? And then the mood shifted. Now, I had no idea of the origin of our bubbles. A soda water maker has stood in our kitchen for years, and every four weeks we swap out the CO2 cylinder for a new one. “But the company Sodastream produces in a Jewish settlement in the occupied West Bank. This is illegal under international law, and must be boycotted for ethical reasons,” our guest said. I swallowed. After all, I am part of the problem: the loading of cartridges in the supermarket costs €5.99, meaning I pay around three cents for the bubbles in one glass of water. What was this company who had disrupted my dinner? Could jobs be bad? What was really going on there?

On location, biblical names are everywhere. “Maale Adumim, Israel, Judea and Samaria Region” is the name of the place where SodaStream operates, according to the navigation device of my rental car. For some, the stretch of land is the occupied West Bank; for others, Judea and Samaria from the Old Testament. A grey tunnel beginning in Jerusalem leads us there before opening up to a wide highway, along which our little car speeds within minutes to Maale Adumim; altogether, it is only 16 kilometres from our hotel to the settlement. The shimmering rocks give the place – home to 38,000 inhabitants – its name: ‘Red Ascent’. The gabled roofs of the houses are also carmine red, with external walls in gentle vanilla. On Derekh Kedem, the main street, there is a beach boulevard without a beach. It is a city that shines from afar.

In contrast, Maale Adumim is nowhere near as visible in SodaStream's annual report to the US Securities and Exchange Commission from May 2014, where it is listed as simply one of the NASDAQ-listed company's many locations. The majority of their production facilities are in Israel, “one of which is in the disputed territory sometimes known as the West Bank”. Page 21 is where the reader first learns that this factory is two and a half times as large as all of SodaStream's production facilities in Israel proper combined. In 2013, the German market alone used 5.5 million SodaStream cartridges, which amounts to 300 million litres of sparkling water. If you want to fizz your water, it’s hard to avoid SodaStream. The company is the global market leader.

The land around the settlement is barren, but Maale Adumim is lined with palms and grassy areas. Everything appears well ordered, and many houses are adorned with fences from ground level to window height. The air is perfumed with the smell of thyme and jasmine. The settlement is like a fortress version of the Garden of Eden. Down the slope, less than 200 metres away, another world reveals itself: next to a sewer pipe, corrugated iron huts that belong to Bedouins. Birds chirp from above, while a donkey's bray penetrates up from below.

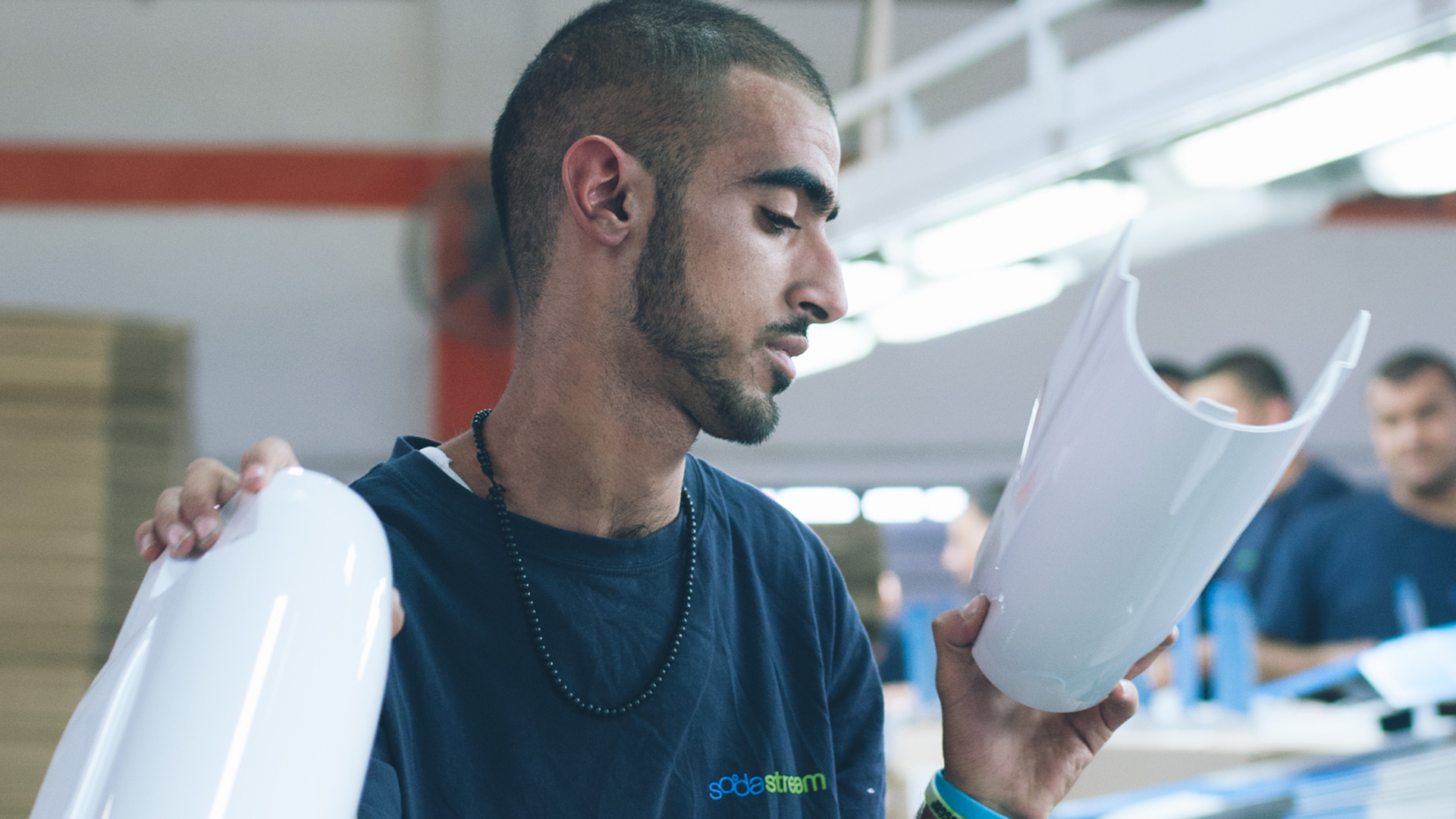

The SodaStream factory gates open onto the south side of the settlement. At the end of 2015, it will close and move to the Negev Desert in the south of Israel. The company management says this is to concentrate production processes elsewhere. The boycott movement against settlement products says it is to evade international pressure. In large halls, workers stand at conveyor belts wearing blue company shirts – men and women, Jews and Palestinians. They appear busy and absorbed, but also relaxed. They produce 4,000 machines here per day. At a workbench at the edge of Production Hall 1 sit 10 Bedouins from the Negev, currently being inducted into their new jobs. If the site here does in fact close, the Bedouins will be able to continue working in the new factory in Lehavim, as they live nearby.

We are able to move freely and speak to anyone we like – no one is keeping tabs. “We have obligatory 12-hour shifts, which is definitely exhausting,” says Muhammed from Ramallah, who is currently packing bottles into cardboard boxes. “But I'm happy to do it. That way I earn more money. After eight hours the wage goes up by half.” Hanan, a woman in her mid-twenties from the Palestinian town of al-Eizariya, praises the work climate, flat hierarchy, and opportunities for advancement. “We all get on well with each other here.” The majority of those we spoke to indicated that they had worked here for over a year. No one wants to talk about politics. “I am satisfied here,” we hear frequently, and “Let's leave that outside.” One person says: “I take the bus 35 kilometres every day from Hebron to the factory. It would be 50 kilometres to the new one in Lehavim. Of course, I would do that too.”

Observing the employees and the way they peacefully go about their work in the halls, nothing seems to be amiss. But does this fit with what takes place outside these walls?

During the search for the Maale Adumim town hall, Scharon points the way as he nudges his daughter on the swings at a playground. “We have been living here for five years, due to the children,” he says. “The rents are cheaper than in Jerusalem and there are good daycare centres and schools.” Does he think that this is occupied territory? “No, this is not a settlement. We are not here for political or religious reasons.” And how is it with his Palestinian neighbours on the outside? “I can't go there. If they were to renounce terror, then they would be able to live like us. But they don't want to do that, and therefore we have nothing to do with them.” Scharon, 34, an army officer, shakes his head. “In comparison, if the Palestinians come to us here in Maale Adumim, they need not be afraid. We are more humane.” 3,500 Palestinian families support Maale Adumim – 500 Palestinians from the combined West Bank work at SodaStream alone. Scharon carries his daughter home. This evening he is meeting a friend for a beer in Jerusalem. In Maale Adumim there is only one bar, and it is usually empty.

Benny Kashriel stands at the window of his office in the top floor of the town hall and points outwards. “Can you see this hill?” he asks. “When we came here, there was only desert. To date there is still no agriculture. Nothing.” Benny Kashriel has been the mayor of Maale Adumim for 25 years, and belongs to the first generation of settlers.

When we came here, there was only desert. To date there is still no agriculture. Nothing.The settlement was founded in 1976, in the wake of the Six-Day War of 1967 and the occupation of the West Bank. The industrial area Mishor Adumim was intended to serve the economic development of Jerusalem; Maale Adumim functioned in the beginning as the ‘workers’ camp’ of Mishor. As a precautionary measure, the Israeli authorities confiscated seven times as much land as the workers’ accommodation required. Only 0.5% of this land was privately-owned Palestinian land – the rest was public land, going back to the Ottoman Empire era. Since then, the settlement has grown steadily towards Jerusalem. “Our natural growth is 600-700 inhabitants per year,” says Benny Kashriel. “But due to the pressure from Europe and the USA, we are only allowed to build 90 homes per year.” He sounds both bitter and calm at the same time.

Until the Six-Day War, the area had been annexed by Jordan, frustrating Palestinian efforts to establish their own state alongside the state of Israel, founded in 1948. According to international law, an occupier is a custodian and may not create permanent precedents. Public land is also to be protected. In the case of Maale Adumim, an interministerial committee of Israel justified the confiscations with the claim that they were serving the public interest, so that both Jews and Palestinians could use the land.

Benny Kashriel has no contact with his Palestinian counterparts. “We pursued cooperation with them, saying, ‘Let's put aside politics.’ But they are too afraid of Hamas and the Palestinian government

Benny Kashriel has no contact with his Palestinian counterparts. “We pursued cooperation with them, saying, ‘Let's put aside politics.’ But they are too afraid of Hamas and the Palestinian government in Ramallah.” When the mayor speaks of the future, he goes into raptures. “We could initiate a binational industrial area and joint tourism projects.” In an occupied territory? “Rubbish. It did not belong to the Palestinians, not before the Six-Day War and not 10,000 years before that. It belonged to Jordan and before that the Jewish nation and King David.” It is a view of the past full of holes - but Benny Kashriel is not a historian but rather a settler, one who makes history.

The others in this story are right next door. From the base of Maale Adumim an asphalt street leads to Eizariya, past an Israeli armoured police car. The town and its 18,000 inhabitants are a stone's throw away. At the other end of this solitary access road, through Eizarya, stands the eight-metre-high wall of reinforced concrete that separates Israel from the West Bank. Thick black smoke swells around the town's entrance. Masked youths have pulled tyres onto the road and lit them on fire, and hold stones in their hands that they have torn from Israel's ‘separation barrier’. They are waiting for the Israeli police, who will not come. The Palestinians are blockading themselves. A mute protest, a ritual. Only the fruit vendors remove their cartons from the street, cursing: the smell is getting worse.

One kilometre further towards the centre, men sit in front of the Murabitin mosque, with chains of beads slowly running through their hands. “Those who work for SodaStream have hit the jackpot,” says Muhammed Saad. The official unemployment rate in the West Bank is 19%, but it is going up. “No one likes the settlement, but everyone has to think of their family first.” Muhammed Saad wears his finely clipped dark grey moustache with pride. A strong, wiry man in his mid-fifties, he sits idly in the shadow of the midday sun. Did the Palestinian leadership not call for a boycott of the settlements? “Ach, then Mahmud Abbas should give us work!” But the president in Ramallah seems far away here. “If SodaStream should in fact close, that would be bad for dozens of families here.”

82% of Palestinians employed in settlements reported that they would give up their work if they were to find a suitable alternative

In a study by Al-Quds University in East Jerusalem from 2011, 82% of Palestinians employed in settlements reported that they would give up their work if they were to find a suitable alternative. For a job in the settlements, one needs a work permit from Schabak, Israel's internal security service. “Thousands of people have it here in Eizariya. My sons don't because they threw stones during the second Intifada 10 years ago. Does that make them worse workers?” asks Muhammed Saad.

According to Israeli NGO Who Profits, 93% of Palestinian workers in settlements are not unionised. The majority eschew all forms of political engagement, as it could lead to the revocation of their licence. Muhammed Saad is the only earner in his family of five. He works for a security firm, a so-called ‘sunrise industry’. Israel does not allow any local police in Eizariya, instead restricting itself to the control of access points. “Criminality is on the rise. Those who can employ private security services for their property.”

Criminality is on the rise. Those who can employ private security services for their property

Around the Murabitun mosque, the concrete is growing taller. Every second building is a construction site on which an extra floor is being added. When Israel occupied the West Bank in 1967, Eizariya lost 61% of its land from the mandate period through annexation. The Israeli authorities rarely grant building permits, and expansion of the city borders is forbidden. Since then, the city has expanded vertically, unlike the industrial area of Mishor Adumim opposite. “The park has the largest land reserves in the Jerusalem region,” says its website. “Land is available at attractive prices.” Low council taxes, loans and a waiving of business tax are promised for the first two years.

The street leads directly to the wall, its concrete blackened by soot. Mounds of rubbish stand on either side. Eizariya is a city in which not much happens. Jerusalem is both very near and very far: the historical, cultural, and economic point of reference for the region here appears like a silhouette in the heavens. Inside is a throng of activity, but outside so many things are out of reach – settlements, restricted military areas, streets. At this height, the West Bank between Jerusalem and the Dead Sea is at its narrowest. Only Maale Adumim thrusts up in between, dividing the land of the prospective Palestinian state into two blocs separated by a few kilometres. From a geostrategic perspective, Maale Adumim is not so insignificant.

With the wall always in view, the street heads south up the hill, reaching the first foothills of Sawarahiya East after five kilometres. In the whitest and most modern house of the village of 8,500, a man sits behind a desk of imperious wood, on which there is only a telephone. With this telephone, Junis Gafar tries to govern something that is near impossible to keep together. “Ask around – someone must have seen something,” he growls into the receiver. The previous night, two solar panels that power the street lights had been swiped.

Junis Garaf is a mayor without police or equipment, but with natural authority

Junis Gafar is president of the local council and a representative of the Palestinian National Authority. He is a mayor without police or equipment, but with natural authority. Like his counterpart Benny Kashriel he has a bushy, parted head of hair, but with the addition of a powerful moustache that wobbles when he moves his head.

“Only the Israeli police may enter a crime scene. And that takes time.” The West Bank is split into three regions: in the cities (Region A), the PNA has responsibility for administration and security, while in the rural areas, daily life is governed by Israeli security forces, and in Region C, where the lion's share of people live (62%), Israel's military has complete control. The city area of Sawahariya East is in Region A, while its surroundings are in Regions B and C. The solar panels were in Region B.

Next to Gafar's desk, portraits of Yassir Arafat and Mahmud Abbas, the late and acting presidents of the PLA, hang on the wall. The local council building was erected with the help of the German Credit Institute for Reconstruction (the KfW). Gafar says the settlements are not the problem, but rather “the sideshows around them, the politics”. Is the mayor in contact with his counterpart in Maale Adumim, Benny Kashriel? The Palestinian shakes his head. “That I refuse. It would only legitimise the occupation.” But so many of his citizens have jobs in the settlement. “What we want, most of all, is our freedom and our dignity.” Does silence accomplish anything?

What we want, most of all, is our freedom and our dignity

Junis Gafar stands up. He points out the window. “That is Sawahariya West, from which we are separated by the wall. My brother lives over there. In theory, I would only need three minutes to reach him by car. Instead, I have to drive via Eizariya, Maale Adumim and Zayyim, which takes at least an hour. Why should I pop in to see Benny Kashriel?” He gets a stack of papers from a desk drawer – the World Bank report on Region C from October 2013. “The way that the area is currently being managed,” it reads, “excludes Palestinian businesses from investments.” If all restrictions were to be taken away – on building permits, entry points, imports and agriculture – the developing activities in Region C would generate $3.4bn per year, equal to 35% of the PNA's GDP. “That's what our country needs,” says Junis Gafar. Who did the land actually belong to previously? “Ask the people in Silwan – they managed it until 1967.”

On the journey in, a building in Sawahariya attracted our attention. The largest in the village, it’s a cement factory standing unused. A man appears from the shadows. “We have been closed for six months,” says Fuad Safi, a powerful man with a lean sheep dog by his side. “15 men worked here – I was with the security detail.” What happened? The 27-year-old points to an Israeli army checkpoint less than a kilometre away. “We couldn't get through the checkpoint and were often not able to deliver the cement on time. We were left with the lot.” Adding to that, the PNA overestimated their taxable income, and so the boss had to close up shop. He now waits for better times.

In Silwan, a bustling neighbourhood not far from Jerusalem's old city walls, a coffee seller gives us a crucial tip: “Go to the mayor at the second crossroad.” He sits behind the counter of his small grocer, dozing. “The owners of the lands in the east? Abu Mahmud al-Abasi knows about that.” In the Ras al-Amud neighbourhood, everyone knows his name, and after a quarter of an hour we are knocking on a wooden door on the first floor of a new building. His daughter opens the door and invites us in. Abu Mahmud al-Abasi enters the living room after a few minutes, the ninety-year-old having previously been asleep. His thin smile is mirrored in the photo portraits of his father and uncles hanging on the wall, all of whom, like him, were mayors of Silwan and custodians of the lands east of Jerusalem.

After the war of 1967 the area was declared a military zone. We were no longer allowed in, and the fields died. And then then the diggers came

“The surrounding area of what is now known as Maale Adumim?” he says. “We fought for it in vain.” Yes, it had been public land, he says. “But also communal property.” Eight black cardboard boxes are stacked right next to the entrance. He grabs one and pulls out old maps and documents. “Here,” he says, and shows us a map from 1945 with many small subdivisions, each of which has a name registered to it. “We mayors registered and managed the lease payments for farms for the British Mandate.” After the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, when the area fell to Jordan, the work continued under Jordan's control. “The region is not very fertile, but sesame and barley grew well.” It was communal land – for centuries, huge fields were cultivated here by citizens of the Ottoman Empire in this manner. When Israel confiscated the land for Maale Adumim, there was no private person who could take legal action. It would have been difficult for a village to act as a plaintiff. “After the war of 1967 the area was declared a military zone. We were no longer allowed in, and the fields died. And then the diggers came.”

What was so simple inside the factory proves almost impossible outside: multiple attempts to get people to speak about their jobs fail

In every village around Maale Adumim, there are Palestinians who work for SodaStream. What was so simple inside the factory proves almost impossible outside: multiple attempts to get people to speak about their jobs fail. This must mean company management has forbidden them to speak to journalists. But we find one who is willing. In an ice-cream café later, in between sips of a lemonade with fresh mint, he says, “The wages and insurance benefits are good. We get three times as much as we would in a Palestinian business.” What disturbs him, however, is the climate of fear. “Anyone who expresses themselves politically is out of there. Our contracts designate us as foreign labour, which gives us fewer rights.” What used to annoy him was the 12-hour shifts, one week during the day, the next through the night. “But that is almost over. 50% of the workers are fired after a year, so that they don't get any work entitlements. I've been there for nine months – I'll do the full year and will then have money for the time after that.” And how do the management of SodaStream view their neighbours' lack of freedom? How do they view themselves in this political environment?

There are many possible ways to react to the situation – a round table, for example, that brings together Israelis and Palestinians and formulates claims for the government in Jerusalem. Daniel Birnbaum smiles wearily at this suggestion. “Call the mayor of Eizariya to a round table? I could do that. And they could also ask me why I don't do this or that. That would have no end. I have a job to do.”

Daniel Birnbaum sits in the experimental space of the headquarters of SodaStream in Tel Aviv. This is where they figure out the new syrups that transform water into soda. The CEO wears his white suit open and rolled up – the 52-year-old sees himself as a peacemaker. “When I started here seven years ago, I took on the first Palestinians. That was very controversial at the time.” He had just come from Nike and had made the brand a market leader in the sports goods industry.

SodaStream settled in Maale Adumim in the 1990s, lured by low rents and subsidies. Nowadays, Birnbaum considers himself a kind of patron of his Palestinian employees. “I fight for my workers – I treat them like brothers.” He once invited them on a bus excursion and traveled with them to the Mediterranean, which many of the Palestinians had never seen. When he accepted his award as exporter of the year, he came to the Israeli presidential palace with a delegation of Palestinians and protested loudly when they were removed to be checked by security.

And perhaps therein lies the problem: when Birnbaum speaks about 'his' Palestinians, there is an element paternalism. “On Facebook today I read a post from one of my employees that read 'Death to Israel.' He was an employee then. I fired him.” And he would do the same if an Israeli posted something similar. What about political activities? “They have to stay outside.” And the history of the settlement region? “No one has lived there since the Kingdom of David.” What about the farms there? “Absolute bullshit.” The Palestinians? “A young nation – 50 years ago, it didn't exist.” And the waiting lines in front of checkpoints? “We also have trucks that have to go through all of the checkpoints. They have to wait too.”

His replies are reminiscent of the mayor of Maale Adumim, albeit more casual in their expression. The hierarchy remains. He says: “Why do you believe this to be an occupation? Jews lived here 2,000 years ago.”

Our conversation comes to a standstill, with a gut feeling that things are not how they should be. And alternatives seem far away. Sentences swarm around in my head: “The settlements are not the problem,” from Sawahariya's mayor Junis Gafar; “Will you join us for a beer this evening?” from Scharon; “We can't go there anymore,” from Abu Mahmud al-Abasi. The factory seems like a wasted opportunity. So little empathy. So many lives lived in parallel rather than together. But the year isn't over yet. Daniel Birnbaum grabs a glass of water from the glass tabletop in front of him, finishes it, and walks out the door.

This article first appeared in German in the 2/2015 edition of zenith. Translation by Ryan Evers.