In July 2015 its members were killed when a suicide bomber's detonation ripped through a crowd of youth activists in the city of Suruç in southern Turkey. Now members of the pro-Kurdish youth organisation SDGF are under attack from their own government.

The last moment Ulaş Alankuş saw his friends alive, he was doling out pamphlets at a rally in the southern Turkish town of Suruç, just beyond the Syrian border. Like his peers, Alankuş intended to cross into Syria to rebuild the city of Ayn Al Arab – known as Kobanî in Kurdish – after the self-declared Islamic State group (Daesh) left it in ruins. Kobanî is just a fifteen-minute drive south of Suruç, and scores of youth were gathered for a press conference to explain their intended journey.

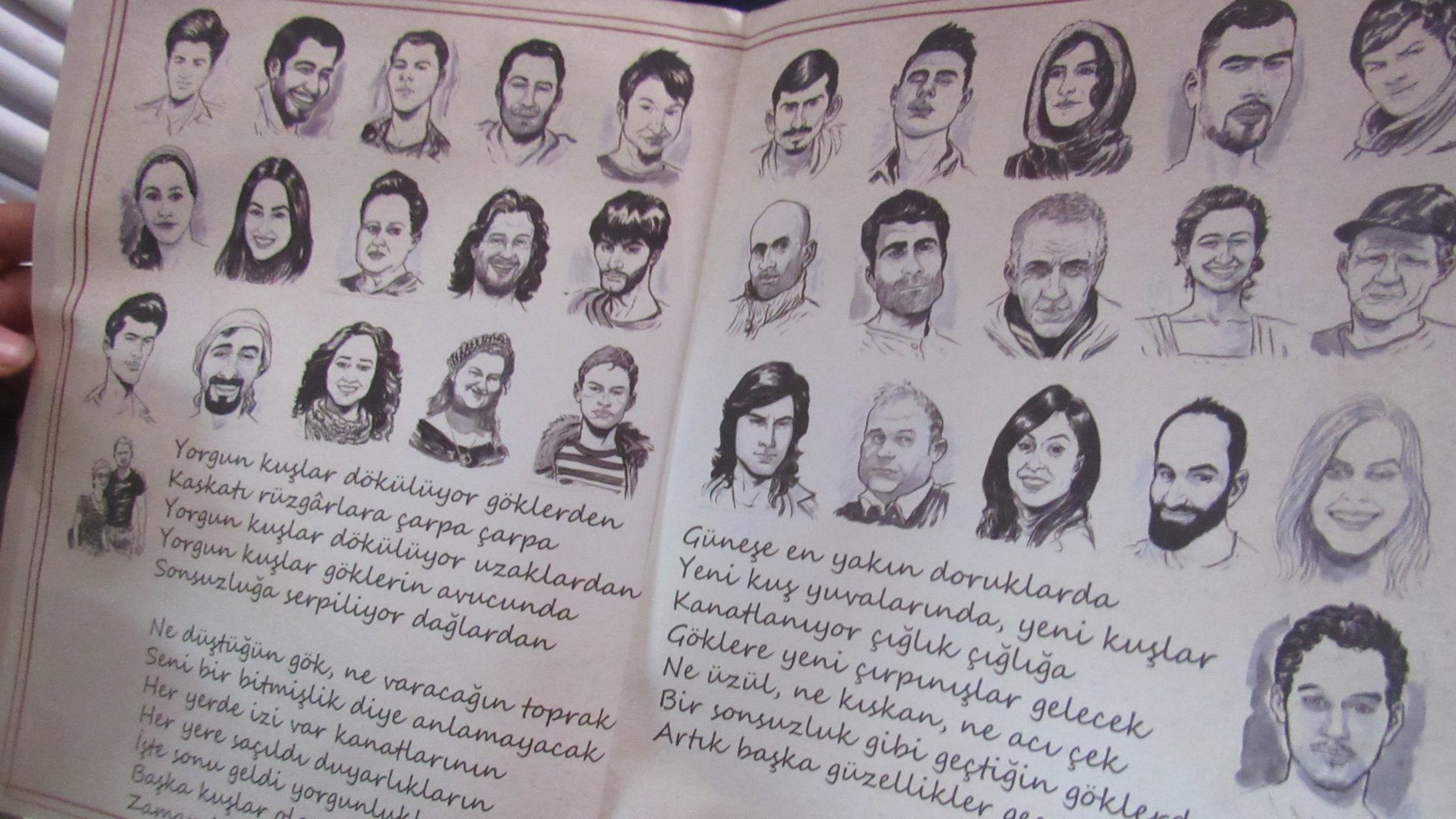

But a suicide bomber changed the course of Alankuş’ life – and his country’s – forever. Thirty-three people died on July 20, 2015, and Alankuş still struggles to comprehend how he wasn’t one of them. The momentum of the blast pushed Alankuş to the ground. Once he got up, he noticed minor burns under his arms and legs. He also remembers feeling nauseated. The stench of burning ashes and blood was all he could smell. “I thought I was the only one who survived,” he says, lighting a cigarette. “The friends I lost did so much for our cause.” He pauses, inhaling and exhaling. “I knew every single one of them.”

Many of the victims of the bombing were members of a pro-Kurdish student movement known as the Federation of Socialist Youth Associations (SGDF), founded in 2004. The group is the youth wing of the Socialist Party of the Oppressed (ESP), a far left political party that some government officials consider a legal front for banned Kurdish organisations. The un-banned SGDF has over 1,600 members; like ESP, they are viewed favourably by the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). Each of these movements supports the political autonomy of Kurds and a socialist republic in Turkey, a political stance that puts them in direct opposition to the state.

The Suruç bombing spiralled the country deeper into turmoil, and even the survivors were not spared. The fragile peace process between the Turkish government and the PKK immediately collapsed, with the latter accusing the government of colluding with Daesh to orchestrate the bombing. The government denied the allegations, blaming Daesh. Seeking revenge against the state, the PKK killed several Turkish soldiers. And rather than stop the bleeding, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, leader of the governing Justice and Development Party (AKP), exploited the attacks to launch a new war against the Kurds.

“[The SGDF] supports the right for everybody to demonstrate in the streets. But the government seems to think that the streets only belongs to their supporters

Erdoğan’s plan was bold. With an election approaching, he was determined to win over nationalist voters, and the war accomplished just that. Yet as the AKP celebrated, the death toll mounted in the southeast. Over 1,700 people had died by January 2016, according to International Crisis Group, a non-profit based in Belgium. Human Rights Watch further reported that the Turkish army was implicated in the unlawful killing of civilians and the displacement of thousands of people from their villages.

Activists who condemned the violence were punished by the state, as part of a larger campaign to stifle dissent. Alankuş was even arrested for protesting at his own high school. The SGDF was under attack again, this time by its own government.

Oppression takes many forms. Ali Deniz Esen, a 21-year-old Turkish activist wounded in Suruç who is now an editor of a pro-Kurdish student magazine called Ozgur Genclik (‘Free Youth’) says police often confiscate copies of the magazine at political rallies. However, that hasn’t coerced him into censoring his content.

“Even though the magazine is legally registered, the government has opened a lawsuit against us,” he tells zenith. “They are angry because we published an article about Rojava. Maybe that’s why [security forces] view everyone who reads our magazine as if they’re terrorists.” Rojava is the Kurdish name for the three Kurdish districts in northern Syria – Jazira, Kobanî and Afreen – now controlled by the Democratic Union Party (PYD), an organisation often called the Syrian equivalent of the PKK. The Turkish government has recently invaded northern Syria to attack the group, fearing that if the PYD establishes a self-governing region on their doorstep, they could help Kurds in Turkey achieve the same thing.

Many pro-Kurdish activists in Turkey view Rojava as a successful democracy, but the truth can be harder to swallow. Human rights groups have accused the PYD of crushing dissent while forcefully evicting Arabs from their villages. Despite the group’s authoritarian tendencies, every member of the SGDF that I spoke to described Rojava as an opportunity to be a part of a revolution. That dream is what Esen almost gave his life for. In Suruç, a piece of metal from the blast punctured his leg, and he wasn’t sure if he would ever walk again. He has fully recovered, but his friends have not all been so fortunate; many died, and others remain paralysed for life. “All of us were aware of the price we might pay [before we left for Kobanî],” he says. “I survived, and now I’m even more dedicated to our struggle.”

Tougher after the coup

The theme of the next issue of Ozgur Genclik will be how the country’s most marginalised communities must struggle together to realise common goals. Any sort of public defiance has become difficult to stage since a state of emergency was imposed following the failed military coup on July 15. That night, Erdoğan desperately urged his supporters via FaceTime to protest in the streets against the coup. They listened to him. And now, Erdoğan is strengthening his grip on power. Sila Kaymak, an 18-year-old activist with SGDF, says that though their group opposed the coup, they have been arrested and harassed more than usual since it happened. “[The SGDF] supports the right for everybody to demonstrate in the streets. But the government seems to think that the streets only belongs to their supporters.”

Five days after the failed coup, Kaymak visited Suruç on the anniversary of the massacre. She and her friends came to pay their respects to those who died. They spent the night in a small house in the village. Fast asleep, they were awakened by loud banging on the door at 2am. Before they could answer, police barged in and rounded up everyone they could find. According to Kaymak, the males in the group were forced into the bedroom by the police officers, while the girls were made to line up against the wall of the living room. At one point, Kaymak asked if she could close the window because she was cold. They refused, and poured a bucket of cold water on her instead.

The police also formed a circle around the boys. They beat them with their batons and kicked them repeatedly to the ground. Many suffered broken bones in the beating. “We didn’t do anything wrong,” says Kaymak solemnly while recalling how helpless she was. “They just wanted to intimidate us,” she adds, grimacing. “They were pointing their guns. We could hear the boys screaming in the room next door. Our friends were crying in pain.” After Kaymak and her peers were taken to the police station, they had a friend slip into the empty house to take pictures of the scene. He took a photo of the broken door and of the bloodstains on the ground. A few days later, Kaymak was released.

Alankuş wasn’t as fortunate – he served eight months in jail on charges of aiding a terrorist organisation. The worst part about his time there was that he was unable to help his peers in the streets, he said. The deadliest incident he was referring to occurred on October 10, 2015. Two bombs were detonated at a peace rally in the capital city of Ankara, killing 103 people and wounding hundreds more. “I felt so desperate and powerless,” he says. “People were dying and I was stuck in prison.”

Insurgents launched three more major attacks the following year. The first two were in Ankara, including one by ultra-nationalist Kurdish militants. The third was a suicide bombing at the entrance of Istanbul Ataturk airport. Daesh was the suspected culprit, though the group never claimed responsibility.

All the while, the state was cracking down on dissent. Activists and rights groups say the use of force has only increased since the state of emergency began. Police arrest activists routinely, holding them for days and weeks at a time. Lawyers complain that there is little they can do for people who the government is after. But that doesn’t seem to faze the SGDF, especially those who have already lost their closest friends. Instead, they continue to support each other regardless of the consequences. That was clear when Alankuş was released from prison, to await his trial. Upon walking out, he saw Kaymak and her friends waiting for him by the exit.

Alankuş awaits his trial; if convicted he could serve several years in jail, but he doesn’t seem anxious about the outcome. Like the rest of the members of the SGDF, he insists that the price of freedom is worth paying.“Our approach has not changed. We understand how cruel the government is. But those who hate us don’t own the country. The streets belong to all of us.”