In a nightclub in Tunis, a strange ritual is carried out where Libyans toss money to a singer, to sing the praises of their towns. It seems peace can be found at the cabaret – for a while.

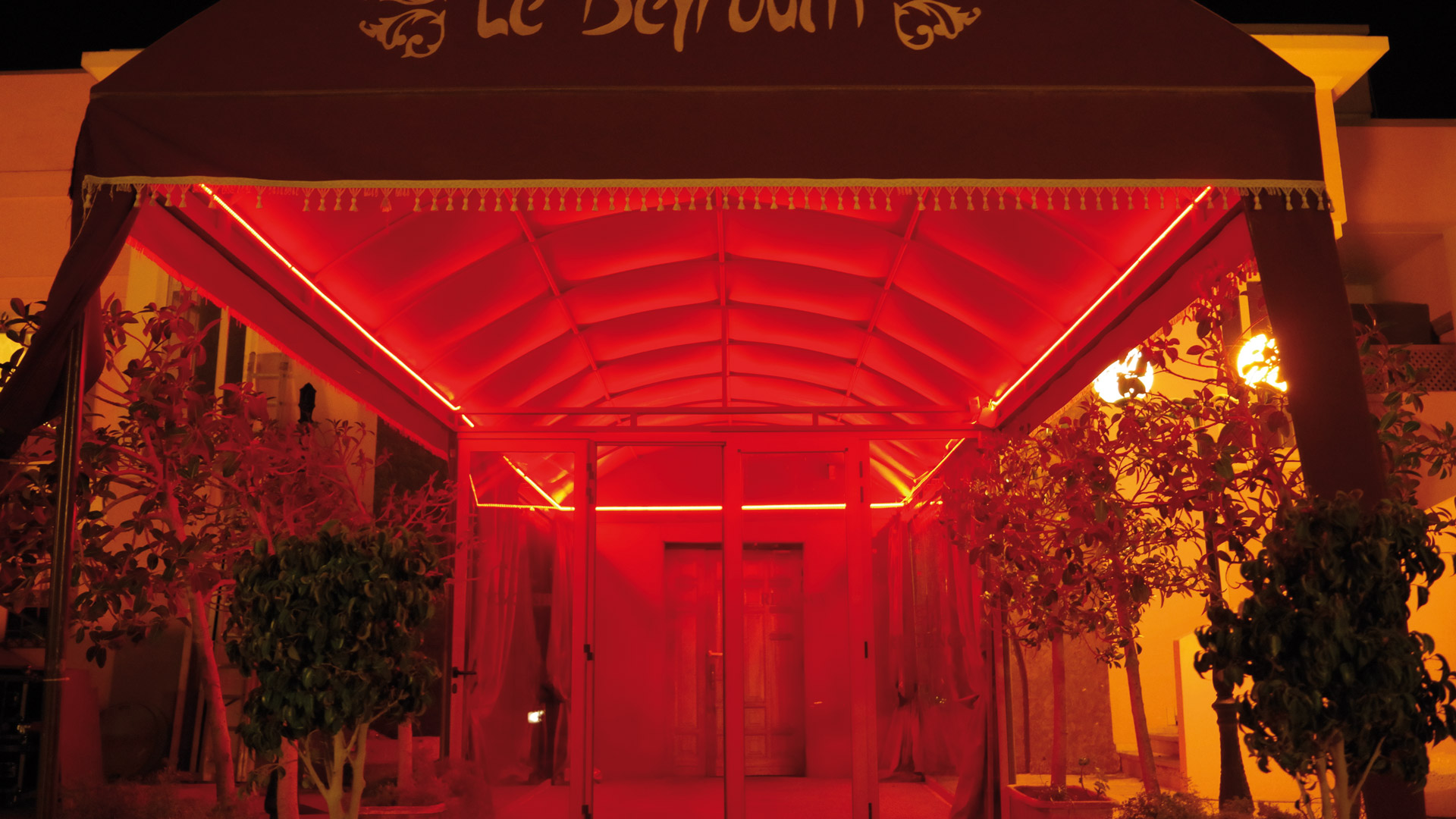

The bouncer opens up the wooden gate and greets us in his Tunisian dialect: “Welcome to Layali Beirut.” We walk through a dimly lit corridor with red velvet walls that give the feel of a 1930s Parisian brothel. What appears to be a sex worker, slightly overweight and wearing a pink tiger-print mini dress, the sides of her breasts showing, stands at the corner of the lounge being flirtatious and smoking a cigarette. Red velvet walls, red carpets, red chairs, red tablecloths – even the chandeliers are red. It is almost 2am and the lounge is half empty. Concerned that it is too late, we are told by our smiling waiter: “The night is still young.”

Sure enough, more people (mostly men) start pouring in, until the place is packed. One after another, singers take to the stage and perform. Bottles are served in ice buckets topped with candle sparklers. The idea of visiting the cabaret came after we heard endless stories about how rich Libyans with extravagant yet tacky taste behave in such places. The stories are confirmed by what we observe, and the scene is so entertaining that we end up going there not once but twice.

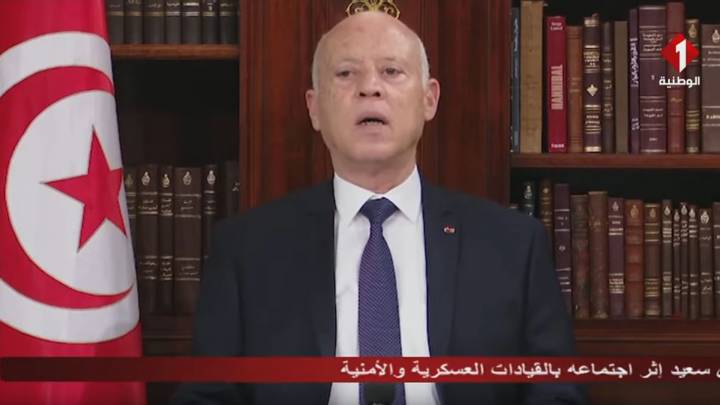

Some background: In 2011, Libya followed in the footsteps of Tunisia and Egypt’s revolutions during the so-called Arab Spring, but in the case of Libya the revolution turned armed and bloody. Eight months after it began, Muammar Qaddafi was overthrown. But then the towns and factions that overthrew him became polarised, divided along ideological, political, regional and tribal lines; in 2014, Libya’s current civil war broke out.

Looking closely around Layali Beirut, each table represents a town or city, and consequently the political affiliations of Libya’s many warring factions. According to regular costumers, even Salafists make an appearance from time to time; ISIS seems to be the only faction that is not represented.

The way it generally works is that singers start to make their way from the stage, around the tables, followed by a man holding a bucket. Each table starts throwing money, for which the singers will give a shout-out to their respective towns, tribes and in some cases even their favourite political player. The bucket guy collects the money as it’s thrown; as the singer moves on to the next table, so does he.

Like its politics, Libya’s financial problems are echoed in the Tunisian cabaret. The country, once flush with oil money, is now crippled by a financial crisis and cash shortages caused by its sole dependence on oil exports, which have largely been cut off by the conflict, not to mention the effects of ongoing civil conflict itself. According to the regular costumers I speak with, Libyans are not the spenders they once were.

But still they open their wallets. The first night we visit, proceedings kick off with a half-naked blonde singer crooning, “Long live Libya, long live all Libyans.” One song after another, she walks her way through the tables giving the shout-outs, while the bucket guy collects the falling money. Things are slowly moving, but still not living up to the stories we’ve heard. My colleague decides to stir things up by throwing a 50 dinar note (20 euros) and asking her to call out the name that makes things interesting: “Greetings to Tawergha, beautiful Tawergha.”

The inhabitants of Tawergha were expelled and dispersed in 2011 in revenge for the siege of Misrata. The tables immediately become as polarised as the political scene in Libya. The notorious money throwing competition is on. Each shout-out to a town affiliated with Dignity (one of Libya’s warring factions) is matched by another to Dawn. “Long live Souq Al Jouma. Long live Tripoli.” “Long live Zintan.” “Long Live Misrata.” And so on.

The stunt my colleague pulls gets him the attention of the whole place. The pro-Dignity drunks praise him for it and warn him of the presence of the “enemy” at the cabaret. The pro-Dawn drunks tell him he shouldn’t have started fitna at the cabaret.

But by the end, with all participants having partaken heavily of the booze, the factions have decided that Libya is one and started throwing their money to this ideal. The whole episode has been incredible to watch. The raw emotions provoked by alcohol have created an unlikely healthy ‘dialogue’. The Tunisian cabaret seems to have succeeded in providing what the UN’s peace talks have failed to: unity.

The second night

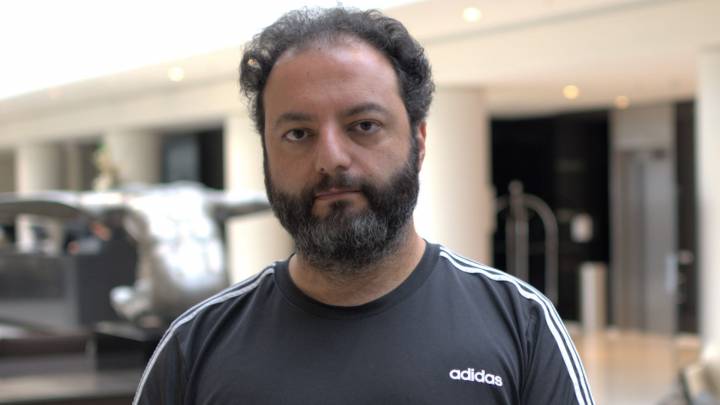

On the second night, a new character emerges – let’s call him Mootez. He’s a friendly Tunisian smuggler from Ben Guerdane who knows almost everyone at the cabaret. The waitress hugs him; the star singer gave him a special shout-out: “Habibi Mootez, I miss you!”

His table has four middle-aged men, including a Libyan partner from the south, two bottles of Grey Goose vodka, a bottle of Chivas, and a number of women who appear to be sex workers. He and his Libyan partner send shout-outs and bottles of Champagne to the other tables, and to the singers on the stage. Mootez is unchallenged; he owns the night now.

Meanwhile, the rest of the tables continue with their money throwing competition; as self-appointed ambassadors of their towns, it is a duty to come out on top. “Long live Haftar,” a chanteuse sings into the microphone, referring to one of the most controversial figures in Libya, followed by “Benghazi”. This alerts the table in front of us. “THEY SAID HAFTAR!”

This heats up the competition, clearly causes consternation, and divides tables along (mostly) regional lines – east, west, but one can’t help but notice the lack of representation of Libya’s south. “The south is always forgotten about, even at cabarets,” a friend jokingly says.

This tension, and the focus on Libyans beating each other at the cabaret wars, is diverted by the appearance of a non-Libyan, a Saudi Arabian. Though not really as committed to beating the rest at throwing money – he more likely wants to hear a special shout-out to his country – he throws a bundle of cash, one note after another, in an endless motion of giving 20 dinar notes to the singer.

She doesn’t seem to want to leave that table. “To the beautiful youth of Saudi Arabia,” she sings. After a while, Mootez feels responsible for winning this for the shattered Libyan nation; he struts over to the Saudi man’s table and throws some money on the singer, bringing the focus of the night back to Libya.

The theory that a foreign enemy can unite a nation has been proven, albeit in a small cabaret experiment. In a show of unity driven by twisted motivations, Libyans start asking for songs about Libya, rather than their own towns. It is now 6am and the cabaret is as alive as ever, until chants of “Haftar” make it tense once more. And with the common enemy gone, Libyans are back at each other’s throats. Mootez, the cabaret equivalent of UN envoy to Libya Martin Kobler, makes his rounds of peace again and brings the happy atmosphere back.

By the time we walk out through dimly lit corridors, the gates open to the sight of a Porsche with Libyan plates driving off, the sun is up. On the drive home, I can’t help pondering the scenes I have just seen inside and thinking that Tunisian cabarets could be the platform for the dialogue the UN aspires to hosting – or the opposite, depending on the level of intoxication.