Cultural activities, artistic projects, the promotion of inter-cultural and inter-religious dialogue can help prevent and reduce violent extremism writes Dr Asiem El Difraoui.

In their Joint Communication “Towards an EU strategy for international cultural relations”, the European Commission and the European External Action Service (EEAS) recognise that many European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) countries face protracted challenges such as political tension, economic upheaval, violent radicalization and continuous migratory flows. The Joint Communication also states that, in this context, cultural cooperation and exchange on cultural policies can contribute to the stabilisation of these countries.

Culture plays a central role for social cohesion and civil peace. The ENP (European Neighbourhood Policy) implies a long-term engagement of the European Union (EU) with its neighbours while simultaneously considering their pressing needs. Yet, and as underlined in the Joint Communication, the most urgent challenge in many countries of the Neighbourhood is stabilisation on political, economic and social levels. As causes of such instability often reside outside the security domain, the EU’s approach must seek to comprehensively address sources of instability across sectors.

Poverty, inequality, a sense of injustice, corruption, weak economic and social development and the lack of opportunity, particularly for young people, can be sources of instability, steering a sense of vulnerability that can lead to radicalization and violent extremism.

Within this context, we believe that strengthening cultural relations and consistently supporting the cultural sector and its civil society actors in the region can contribute significantly to the enhancement of ENP priorities – namely the creation of employment through inter alia the promotion of cultural and creative industries, the reduction of factors driving to migration, the enhancement of security and social stability in the region, etc. – and hereby support the prevention and the countering of violent extremism.

According to an Ipsos poll for the Anna Lindh Foundation, 54 percent of the concerned populations in the Southern Mediterranean believe that cultural and artistic initiatives are a very efficient tool to prevent and deal with conflicts and radicalization, while further 22 percent believe that such initiatives are at least somewhat efficient.

This poll also highlights that meeting and interacting with people from Europe positively influenced the views and perceptions of Europe and the Europeans for 48 per cent of the respondents from the MENA region.

Thus, fostering intercultural dialogue and exchange between Europe and its southern neighbours could decisively influence mutual understanding and common interests, which will counter radicalization processes in the long run. This dialogue, if embedded in a regional, sustainable and comprehensive form of cultural support, will also help countering increasing polarization within societies.

Preventing and countering violent extremism

The important role culture and arts can play in preventing and confronting violent extremism, and in mitigating its consequences, has only recently become a topic of discussion among experts and practitioners and is slowly developing into an area of research in Social Sciences.

We would suggest a strong relationship between flourishing cultural spheres and the reduction of violent extremism. Arts, culture and cultural exchanges contribute strongly to the creation of individual or collective social capital by building and strengthening social networks. Social capital, in the approach of several social scientists and counterterrorism experts, is one of the most crucial variables for individual and collective resilience.

At EU level, the recently released “Strategic Approach to Resilience” is aiming at strengthening, among others, the capacity of societies, communities and individuals to manage opportunities and risks in a peaceful and stable manner, and to build, maintain or restore livelihoods in the face of major pressures.

In this view, it is crucial to go beyond crisis containment to develop long-term strategies and approaches to vulnerabilities, while focusing on anticipation and prevention. In order to reach such goals, other methodologies and actors are needed.

In a long-term perspective, culture plays a central role for social cohesion and civil peace. Through the active participation of civil society, local actors are empowered and take actively responsibility for the development of their societies.

Cultural identity

Asserting a cultural identity – here defined as a dynamic and open identity – as well as a rich and diverse cultural heritage creates resilience to extremist ideologies and their narratives that promote fallacious and deceitful concepts of, for example, Islamic identity or of extreme nationalism.

Indeed, jihadists, even more than other extremist groups, have constructed what can be considered a grand narrative, a closed worldview. To do so, they have hijacked Islamic history and key symbols and concepts like jihad itself to portray jihadists as the only “true community of believers” and promote a salvation myth. A myth that, in its core, promotes the idea of becoming a “martyr” through suicide attacks – a Machiavellian weapon for asymmetrical warfare. It is crucial to confront the jihadi imagery as extremists have not only annexed Islamic visual symbolism but also flooded the Internet with their horror movies inspired by the worst productions of Western societies.

Fine arts and literature can counter the jihadi narrative, for example through the promotion of the numerous achievements of Arab-Islamic sciences, architecture, poetry, literature and music, to show that at its apogee, Arab-Islamic culture was very open, tolerant and strongly enriched by Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian-Persian influences. These facts are unknown to the majority of younger Arabs.

The promotion of culture can constitute a strong source of pride that can counter extremist narrative. As several young Egyptians and Tunisians aged between 18-25 pointed out in interviews, there seem to be, among their age group, a rejection of the present and a longing for the mythical time in Islamic history that the jihadi ideology projects.7 The achievements of the Arab-Islamic culture are an important tool to refute the historic and cultural distortions of extremism.

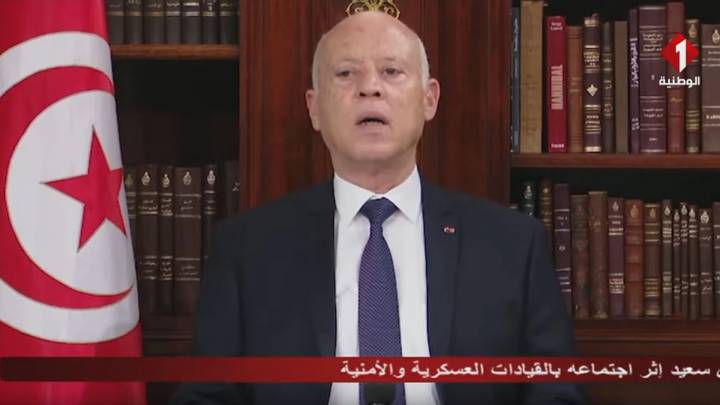

Culture and artistic projects embedded in more recent history can likewise serve as a useful preventive measure. For instance, a remarkable exhibition in Tunis entitled “The rise of a nation”, organized by the Rambourg Foundation, displayed for the first time ever Tunisia’s Ottoman history and diversity. Hereby, it filled the historical and cultural gap of a culturally diverse period, which has been obscured for a long time by the Tunisian authoritarian rulers, in order to legitimate their own regimes.

Contemporary cultural creations can promote free and critical thinking and create narratives that counter the collective uncritical spirit of extremist ideologies, especially if creatively disseminated through the media. Youth culture too can create pride, but also constitute a very efficient means of expression for frustrations and grievances, allowing to reach a wide audience.

As a reminder, rap and graffiti artists played a crucial role at the beginning of the transformation processes in the Arab world, especially in Tunisia and Egypt. In fact, they still play a crucial role, as the example of the Tunisian rap song “Houmani” confirms. Its lyrics highlight the major problems confronting Tunisian society: youth unemployment, poverty, lack of opportunities, police violence and the resulting escape into drugs. The song has about 28 million views on YouTube – a substantial number in relation to the 10 million inhabitants of Tunisia.

Other examples of contemporary culture in the region, such as Arab music contests on satellite TV, illustrate that Arab artists can create positive role models and attract a huge number of followers and fans, and thus help to make extremism less attractive. A further example is the mobile exhibition entitled “Le monde entier est une mosquée” that was on show as part of the annual Jaw Festival in Carthage, Tunisia, where artists expressed themselves both in an open and provocative way, and tried to occupy public spaces that have for too long been left to extremism.

Cinema too can clearly play a large role in countering polarization and preventing violent extremism. The films of the Egyptian filmmaker, Amr Salama, produced under difficult censorship conditions, are an example in kind. In the comedy “Excuse my French”, he counters religious stereotypes and extremism with the tale of a Christian boy in an exclusively Muslim school.

Levels of prevention

Social scientist as well as counter-terrorism specialists distinguish between three levels of prevention: Primary prevention, addressing societies at large; Secondary prevention, targeting particularly vulnerable groups; and Tertiary prevention, focussing on already partially radicalized groups and individuals.

Artistic expressions, cultural projects and enhanced inter-cultural dialogue can operate as useful tools on all three levels. The Tunisian government, for example, seems to take this into account. The summary of the Tunisian cultural policies survey of January 2017 lists the changes and updates implemented in the Tunisian cultural policy from early 2015 to late 2016, and how these connect to changes in the Tunisian society and politics. The most prominent developments include the government roping the cultural sector in prevention and counter-terrorism programmes, while making the cultural sector more independent from government work and increasing the number of civic cultural initiatives.

Culture is the best weapon against backwardness, darkness and terrorism. The Tunisian civil society organisations are also getting increasingly active. Olfa Terras–Rambourg, the initiator of the Rambourg Foundation that will create the “Centre des arts et des metiers” in the Mount Smema Region, a hotbed for Jihadism in Tunisia, explains that her initiative is motivated by a strong demand from within the population, “who wanted culture”. She herself sees the advancement of arts and culture as being “at the heart of the struggle against exclusion and extremism”. In 2013 already, the 48-hour arts event “de Colline en Colline” took place in three towns in northern, central and southern Tunisia where Islamist extremists were recruiting. The involved artists wanted to consciously confront extremism with art.

A more recent example is the Jabal theatre in the very marginalised region of Kasserine (Tunisia), where there is a high proportion of jihadi sympathisers. The director of the theatre, Adnen Felali, a 42-year-old teacher, uses traditional culture and drama to oppose the jihadi narrative of violence, and tries specifically to reach children, who are “the future of our country”. A young Tunisian woman attending the Jabal theatre, herself severely wounded by landmines laid by the jihadists or the security forces fighting against them, is convinced that “culture is the best weapon against backwardness, darkness and terrorism.”

Tunisian civil society, with the support of the Tunisian government, is hence already operating on primary and secondary prevention. Other examples show how culture in various forms has also been used in terms of tertiary prevention, for the rehabilitation of extremists for example, as demonstrated with jihadists in German prisons.

Even if the European experience can often not be directly implemented elsewhere, it is a useful indicator of what can be achieved. More generally, there are huge possibilities in terms of art therapy, for example for children who have been traumatised by the extremely violent conflict in Syria. Lebanon-based NGO Action4Hope works closely with displaced people who have fled from wars and violent political turmoil, providing them with the means for freedom of expression, healing, art therapy, creativity and communication.

The Artistic Director of Clown Me In, an NGO from Lebanon, Ms. Sabine Chouchair, says clowning, for instance, is a powerful tool to take youth out of extremist ideology circles. “I have worked with unemployed youth in northern Lebanon, which is a hotspot of sectarian violence. Most of them were either fighters in the civil war or potential recruits by the militant groups. We turned the cafes — where they used to hang out — into cultural cafes, and organised clowning and theatre performances.”

Focus on the media

A comprehensive and creative media strategy reaching a large audience would contribute to decrease polarization, which itself is a crucial push factor to non-violent and violent extremism. This is not only true in terms of polarization within the societies of the southern Mediterranean or the growing cleavage between Europe and its southern Mediterranean neighbours, but also applies to our own societies in Europe.

Media coverage, which today focuses largely on terrorism, destruction and the refugee crisis, creates fear among Europeans and pushes a considerable number of them to populism, islamophobia and sometimes violent extremism. This type of media coverage is also perceived as extremely stigmatizing by the people of the southern Mediterranean and can be considered as a trigger for violent extremism itself. Efficient media distribution of arts and culture produced in the southern Mediterranean would bring European and Arab audiences and their dynamic civil societies closer.

It would help to counter the processes of “othering” and stigmatization that instils fear and leads to polarization, and vigorously illustrate that we have more in common than what divides us.

Dr Asiem El Difraoui is a political scientist and author specialised on the Southern Mediterranean and the Arab world. His specialities include jihadism, Arab media and Arab-youth culture. He is a cofounder of the Candid Foundation.

This paper was written with contribution from Sana Ouchtati, an independent consultant on international cultural relations.

This paper was commissioned by More Europe and the Goethe-Institut. You can read the full text with footnotes and recommendations here.